Hank Aaron at Duncan Park? Probably!

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Did he make a stop in the Hub City on his way to The Show? Did the man who broke Babe Ruth’s home run record and became the greatest Braves player of all time set foot on the Sparkle City diamond? As is true of many issues in pre-integration Black baseball, the answer to this question is a probably reliable “Yes!” but it’s hard to provide the documentation to prove that it is so.

Hank Aaron at Duncan Park? Probably!

Did he make a stop in the Hub City on his way to The Show? Did the man who broke Babe Ruth’s home run record and became the greatest Braves player of all time set foot on the Sparkle City diamond? As is true of many issues in pre-integration Black baseball, the answer to this question is a probably reliable “Yes!” but it’s hard to provide the documentation to prove that it is so.

It is an undeniable fact that many famous baseball players took the field at Duncan Park stadium. Future MLB Hall of Famer Ryne Sandberg played here as a Spartanburg Phillie. So did his fellow Hall of Famer Scott Rolen. Nolan Ryan pitched here when he was a Greenville Brave, striking out future MLB player and manager Larry Bowa three times when they first faced off against each other. Rocky Colavito played here as a Spartanburg Peach. Heck, the whole 1937 New York Yankees—whose roster that year included Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gehrig, Red Ruffing, Lefty Gomez, and Frankie Crosetti, and who were to win the World Series 4 games to 1 against the New York Giants—played here on their way back to the Big Apple from Spring Training in Florida.

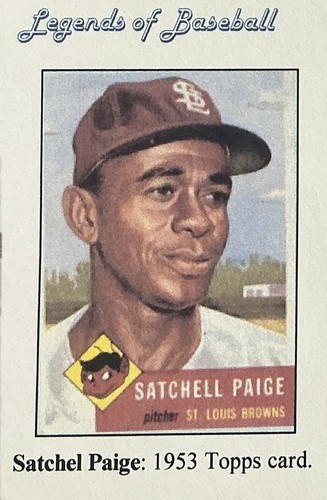

A large number of Negro League ballplayers came to Duncan Park too. Satchel Paige played three innings of exhibition baseball before the old wooden grandstand in the 1960s, and Jackie Robinson brought his barnstorming All-Stars to Spartanburg several times. When Jackie came, he brought his friend and South Carolina native Larry Doby—who broke the color barrier in the American League not long after his pal did with the Dodgers in the National League. Minnie Miñoso sat in the dugout here, as did the legendary teams the Homestead Grays, the New York Cubans, the Atlanta Black Crackers, the Ethiopian Clowns, the New York Mohawk Giants, and lesser known teams in the Negro Major and Minor Leagues from Asheville, Atlanta, Birmingham, Orangeburg, Richmond, and elsewhere.

And what about Hammerin’ Hank Aaron? Did he make a stop in the Hub City on his way to The Show? Did the man who broke Babe Ruth’s home run record and became the greatest Braves player of all time set foot on the Sparkle City diamond? As is true of many issues in pre-integration Black baseball, the answer to this question is a probably reliable “Yes!” but it’s hard to provide the documentation to prove that it is so.

Henry Louis Aaron of course was born in 1934 and grew up in Mobile, Alabama. Like many future Negro Leaguers, Hank was raised in poverty, but he and his brothers played baseball using whatever equipment they could cobble together out of cast-offs, pieces, and materials they fashioned from scraps. One familiar account is that he spent many hours practicing using sticks for bats and bottle caps as substitutes for balls.

Hank did not play organized baseball as a kid, and his high school did not have a baseball team, but he developed on the streets and sandlots into a skilled and powerful player. The result was that in his teens he played for both the semipro Prichard Athletics and Mobile Black Bears. His skills attracted scout Ed Scott, who signed him to a contract with the Indianapolis Clowns in late 1951, for whom he played for three months during the 1952 season.

Jackie Robinson had signed with the Dodgers four years before Hank signed with the Clowns, and the obvious abilities of Black ballplayers had by 1952 attracted many MLB teams to many semipro and professional Black players, many of whom were signed when they were still quite young. Hank’s prowess quickly drew MLB teams, and both the New York Giants and Boston Braves offered him contracts. The Braves sent an offer of $50 a month more than the Giants, so Hank signed with them and was sent to their Minor League Eau Claire, Wisconsin Bears, in June 1952.

It is natural to wonder whether Henry Aaron ever played for the Clowns specifically in Spartanburg during the three months between his signing with them in April and his joining the Braves in June. The likelihood is high considering that the Clowns appeared in Spartanburg a number of times, and Spartanburg Sluggers owner Newt Whitmire was a savvy promoter who brought many Negro Leagues teams to the Upstate of South Carolina. Negro Leagues owners knew that they could make money by coming to Spartanburg.

That is indeed what happened with the Clowns on May 15, 1952. On that date they came south to Duncan Park to play against the Negro American League Philadelphia Stars during the last year of their existence. Hank’s last game with the Clowns was reported on June 10, 1952, by The Indianapolis Star, so he was indeed still a member of the team a month earlier when it played in Spartanburg.

Henry Aaron was only 18 when he played for the Clowns, but he was already well known, not only to the savvy experienced fans who followed Negro Leagues baseball closely but also to casual fans who enjoyed the National Pastime and passed through the turnstiles of big city ballparks just a few times a year or read their city’s newspaper accounts of local games featuring the major players whom everyone had heard of.

Young Hank Aaron was already on his way to becoming one of those stars. The Philadelphia Tribune, the oldest continuously published African American newspaper in the United States, not only reported to its readers on April 22nd that their Negro American League team the Philadelphia Stars was going to play in Spartanburg in May, but also two weeks later reported that in Spartanburg they would play against the Indianapolis Clowns and their “sensational 16-year-old” shortstop, Henry Aaron.

Twelve days after introducing young Aaron in April, on May 27th, a dozen days after they had played at Duncan Park, the paper from the City of Brotherly Love extolled Aaron in especially glowing terms in an article about how the Clowns were dominating the Negro American League. The rookie shortstop was so good that he was being touted as “a sure bet to cop the Outstanding Rookie award in the NAL this season.” He was also described as “the best prospect seen in the Negro Leagues since Willie Mays.” No small praise from the hometown paper of the city whose team was led by player-coach Oscar Charleston, widely regarded as the best Negro Leagues player of his day and a future member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Nonetheless, Henry Aaron was gone, sold to the Boston Braves organization and promptly shipped off to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, by the middle of June. By then he was himself an undeniably legitimate star. In reporting Aaron’s sale to the Braves, The Philadelphia Tribune made clear just how good he was: “All Aaron was doing at the time of his sale was leading the league in batting, runs, hits, doubles, home runs, runs batted in, and total bases. He was third in stolen bases.”

Whether Aaron actually played as the Clowns shortstop before local fans at Duncan Park in Spartanburg is a more difficult question. Both the morning and evening newspapers in Spartanburg had brief notices of the tilt between the Clowns and the Philadelphia Stars at Duncan Park on May 15th, the date the game was to occur. The Herald, the morning paper, also had a notice and a photograph of Clowns star Sam “Piggy” Sands in its issue of May 11th. Other Clowns players mentioned in these accounts were outfielders Henry “Speed” Merchant and DeWitt Smallwood, the latter another young player being scouted by Major League teams. Mum was the word on Henry Aaron in all three of these pieces.

Neither of the local papers had a post-game description of the contest nor even who the winner was (although both The Philadelphia Tribune and the Norfolk, Virginia, New Journal and Guide reported that the Clowns had won by a score of 7-6). No accounts that I have seen give a roster of which players took the field on May 15th or whether Henry Aaron had taken the field. The absence of Aaron’s name does not necessarily mean that he did not play however. Newspapers typically gave short shrift to Negro Leagues games, especially if the paper was a White-owned paper catering to its white audience. On occasions when White papers did cover Black teams, the reports were most often incomplete and frequently inaccurate, a common practice being the misspelling of Black players’ names.

Both the Spartanburg Daily Herald and the Journal and Carolina Spartan were White-owned newspapers, and there was no Black-owned paper locally in 1952. It was hardly unusual that papers catering to a White readership like the Herald and the Journal would fail to have sports reporters whose beat included local Black sports teams, and space restrictions in a paper in a small Southern town would make the coverage of Black athletics even less likely. Spartanburg Sluggers owner Newt Whitmire would also have current and retired Black personalities—both entertainers and athletes—appear with some regularity for promotions at Sluggers games at Duncan Park, but it was not uncommon that the two White newspapers would contain no coverage of these events.

So here’s what I think: since Henry Aaron was unquestionably a paid member of the Indianapolis Clowns in May 1952 and since some Spartanburg fans of Negro Leagues baseball would know at least something about the young shortstop and would expect to see him play when he came to their town, nobody in authority—neither team owners nor their managers nor the promoter who had brought them to Spartanburg—would have had the nerve not to play Henry that night. It is unfortunate that we cannot at this point verifiably document his presence in the game, but all probabilities—plus the anecdotal testimony of many Spartans in the last 70+ years—are pretty convincing. So I have confidence that Hank Aaron was at Duncan Park stadium in Spartanburg on May 15, 1952.

If you were at Duncan Park that evening and saw Hank play, please let me know. If you have a photograph that proves it, that’s even better.

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Author

Dr. Edwin C. Epps is a retired educator with more than forty years' experience in public school classrooms... He is the author of Literary South Carolina (Hub City Press, 2004) and a proud member of Phi Beta Kappa who believes in the value of the humanities in a rapidly changing world.