Did Shoeless Joe Jackson Play at Duncan Park?

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Yes, for sure, but maybe just once. I’ve done some research that confirms it because a friend told me he had, but I had not seen anything in my newspaper database searches for my book about Duncan Park stadium that would have given me a clue.

Did Shoeless Joe Jackson Play at Duncan Park?

Yes, for sure, but maybe just once. I’ve done some research that confirms it because a friend told me he had, but I had not seen anything in my newspaper database searches for my book about Duncan Park stadium that would have given me a clue.

Yes, for sure, but maybe just once. I’ve done some research that confirms it because a friend told me he had, but I had not seen anything in my newspaper database searches for my book about Duncan Park stadium that would have given me a clue.

The game I found just a week ago occurred in Spartanburg on August 11, 1932. Joe played for the Greenville Spinners against the Drayton Mill team. The Spinners were a semipro team typical of those that played throughout the South during the Great Depression and before the outbreak of World War II. Drayton Mill was typical of the Textile League teams whose history has been recorded in Thomas Perry’s seminal book, Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880—1955 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 1993).

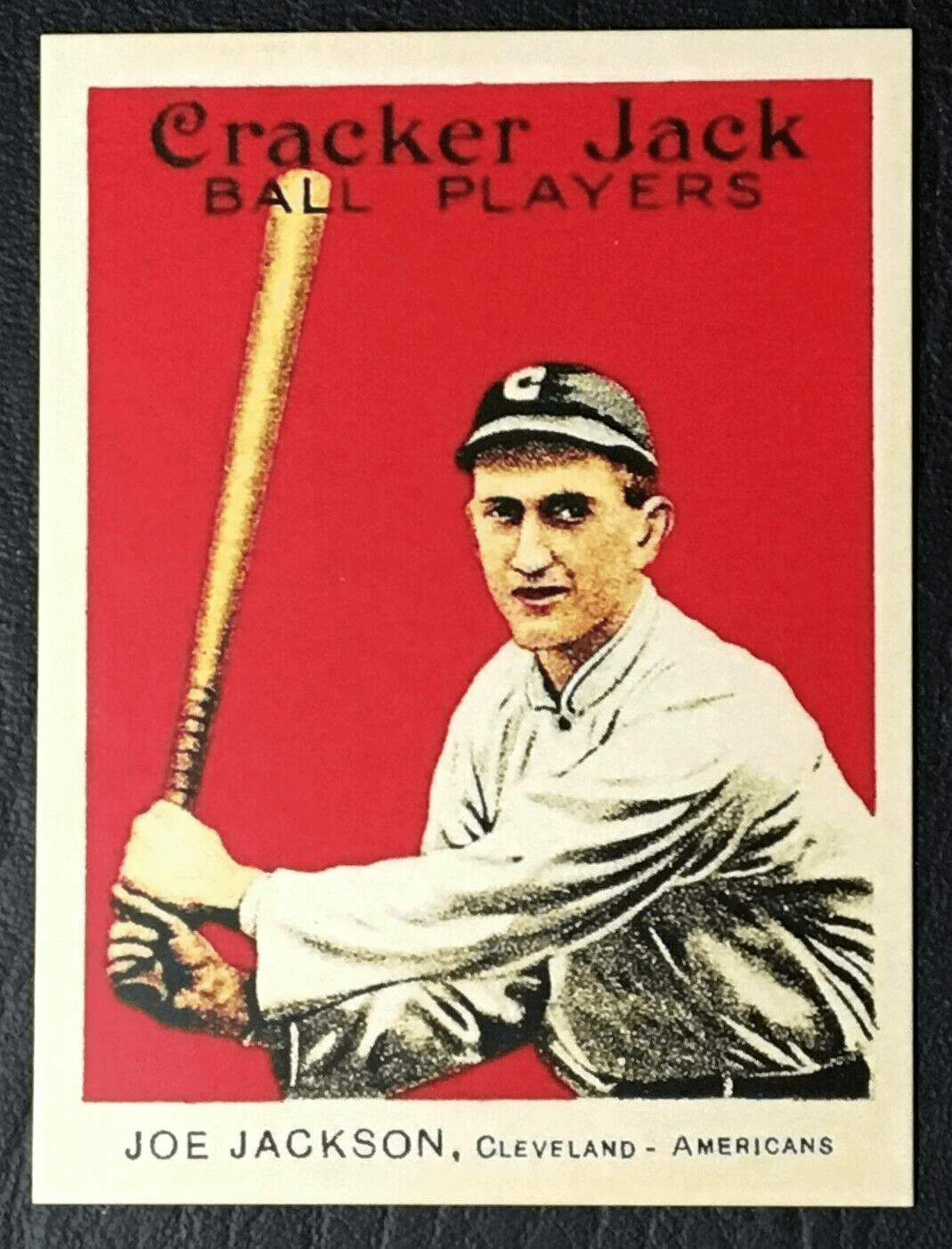

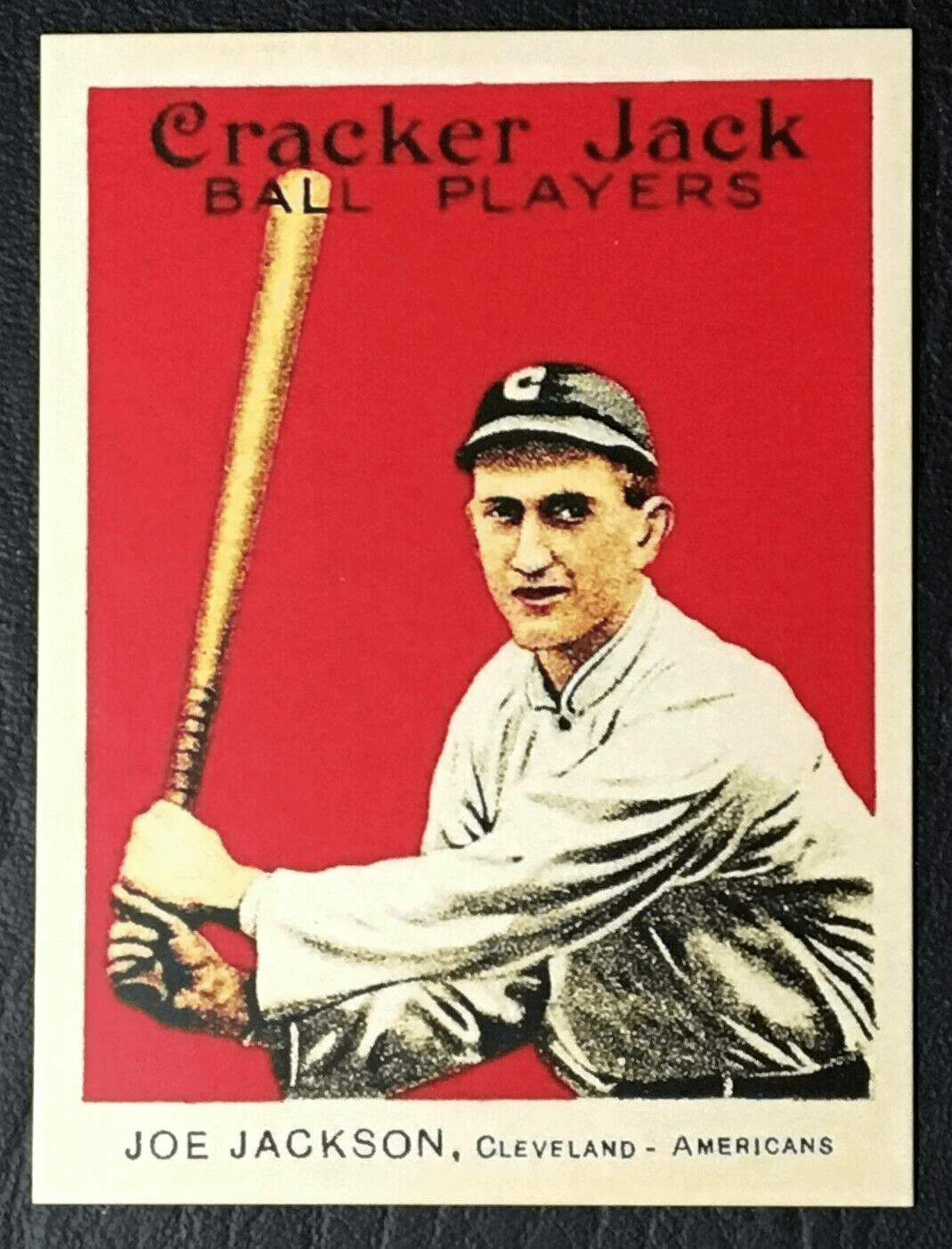

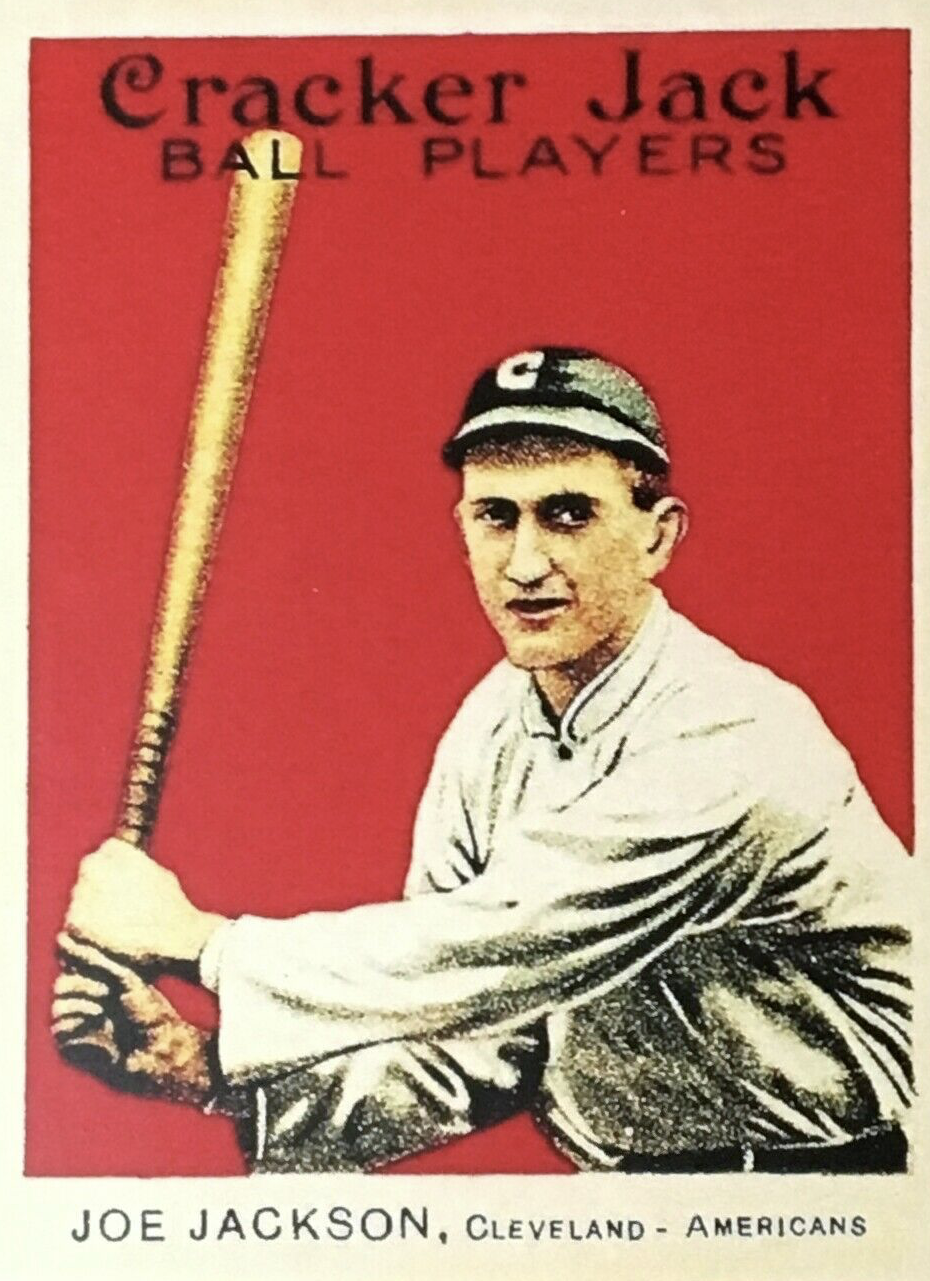

Shoeless Joe had a long history in Textile League baseball, having begun playing for the Brandon Mill team as a 13-year-old in 1900. From there he went on to play for Victor Mill and then the semipro Greenville Near-Leaguers and the professional Greenville Spinners of the South Atlantic League. In 1908 he was hired by Connie Mack and played briefly for the Philadelphia Athletics, then A’s Minor League teams, and was finally traded in 1910 to the Cleveland Indians, for whose New Orleans franchise he played and batted .354 before being promoted to the Bigs. From then through 1914 he played for the Indians and was recognized as one of the best players in Major League Baseball. In 1911 he even hit .408, an average that unfortunately proved second to Ty Cobb’s championship .420.

Joe was traded to the Chicago White Sox in August 1915, where he played until his career was cut short by the infamous 1919 Black Sox scandal, in which eight White Sox players—including Joe—were accused of taking bribes to throw the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. The story is one of the best known in Major League history. In spite of the fact that Joe denied taking the $5,000 bribe he was accused of accepting and the fact that in 1921 a Chicago grand jury acquitted Joe of the charges against him, baseball Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was not swayed. He imposed a lifetime ban from organized baseball upon all eight White Sox players.

In 1922, the year after the Major League ban, Joe and his wife Katie moved to Savannah, Georgia, where they opened a dry cleaning business. After more than a decade Joe and Katie returned to Greenville and opened, first, another dry cleaning business, and then “Joe Jackson’s Liquor Store,” which Joe was still running when he died of a heart attack.

After Joe was banned from the Major Leagues, he was hardly through with baseball. For the next twenty years he played for a variety of “all-star,” semipro, and Textile League teams in Georgia, South Carolina, and elsewhere in the South and even the North, including in Philadelphia late in the summer of 1932, the year of the game at Duncan Park. He continued to play impressively well into his forties and even pitched in a Textile League game when he was 56 and hit a ball off the centerfield fence.

In the summer of 1932 Joe was playing for the Greenville Spinners, with whom he had begun playing “while on vacation,” according to one newspaper account. He had played in Columbia also, and newspapers in Brooklyn and Miami had noted his return to the diamond and reported it to their readers. The Miami News told its subscribers that on August fifth he had guaranteed that he would hit a home run for the Spinners in a contest against a team from Gaffney. Joe delivered: he “hit one over the fence and later hit a savage liner that delivered two runs.”

It was therefore an eager crowd who came to see the Spinners play Drayton Mill, champions of the Spartanburg County Textile League, at Duncan Park. It had been twenty years since Shoeless Joe had played in the Hub City, and many locals remembered seeing him in his prime. So as The Spartanburg Herald reported, “Five hundred fans paid their way into the park and as many more were chased from fence to fence by the cops as Drayton nosed out the Spins 5 to 4.”

Shoeless Joe didn’t disappoint his fans. He went 2 for 4 and hit a “long fly to deep center in the third inning which Burgess barely pulled down, and which would have been a home run with plenty of room to spare in a smaller park.” Wilton Garrison, the reporter assigned to the game, also observed that “Joe still swings with a hard, clean swish and always connects.”

In addition to performing up to expectations and true to his status as a fan favorite, when Joe’s teamwas not batting, he stationed himself out in centerfield “lounging in the shade and talking to a crowd of admiring youngsters.” Although it wasn’t reported, it is also likely that Joe chatted with a good many of the older fans too. After all, as reporter Wilton Garrison verified, “The fans came out to see Jackson.”

In August 1932 Joe Jackson was no longer the svelte professional he had been as a younger man. He tipped the scales at some 250 pounds, and his speed was gone. Nevertheless many spectators who witnessed the Duncan Park game that day knew that like them, the man who wielded the legendary bat “Black Betsy” had spent much of his childhood working in a mill. When he was six years old he began the daily walk to Brandon Mill alongside his father and his siblings, and he continued that trek until he could devote all of his time to baseball. After he was barred from professional baseball by Judge Landis, he spent many long hours individually coaching players like Murphy Grumbles of Brandon Mill. He coached and managed teams too, and he was the player/coach of others.

Like historian Tom Perry says, “Joe’s ties with textile baseball were never really broken.” Even today, 73 years after his death, the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum is housed in Joe’s former home not far from the city mills on whose fields he played and just steps away from Fluor Field and the city of Greenville’s current Class A team, the Drive. Thirty-seven miles down Interstate 85 his ghost still roams the outfield of Duncan Park stadium, the oldest wooden grandstand ballpark in the Palmetto State, where he batted .500 on a hot August day in 1932.

(The Hub City Spartanburgers, the new team in Spartanburg, which will call the new Fifth Third Park home beginning in Spring 2025, are considering giving Shoeless Joe a display post of his own in their stadium exhibition devoted to the history of baseball in Spartanburg.

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Author

Dr. Edwin C. Epps is a retired educator with more than forty years' experience in public school classrooms... He is the author of Literary South Carolina (Hub City Press, 2004) and a proud member of Phi Beta Kappa who believes in the value of the humanities in a rapidly changing world.