The Bronx Bombers Avoid Bombing at Beautiful Duncan Park

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

The Spartanburg Herald predicted a “Big Crowd.” Remembering the packed stands of the previous summer when more than 50,000 fans had attended the Little World Series of American Legion Baseball in the same venue, most locals agreed. The New York Yankees were coming to town, and as a bonus their Minor League team the Binghamton Triplets was going to train in the Hub City during March and April.

The Bronx Bombers Avoid Bombing at Beautiful Duncan Park

The Spartanburg Herald predicted a “Big Crowd.” Remembering the packed stands of the previous summer when more than 50,000 fans had attended the Little World Series of American Legion Baseball in the same venue, most locals agreed. The New York Yankees were coming to town, and as a bonus their Minor League team the Binghamton Triplets was going to train in the Hub City during March and April.

The Bronx Bombers Avoid Bombing at Beautiful Duncan Park

The Spartanburg Herald predicted a “Big Crowd.” Remembering the packed stands of the previous summer when more than 50,000 fans had attended the Little World Series of American Legion Baseball in the same venue, most locals agreed. The New York Yankees were coming to town, and as a bonus their Minor League team the Binghamton Triplets was going to train in the Hub City during March and April. The Cincinnati Reds were coming to town too to open their spring training exhibition schedule against Binghamton on April 10th.

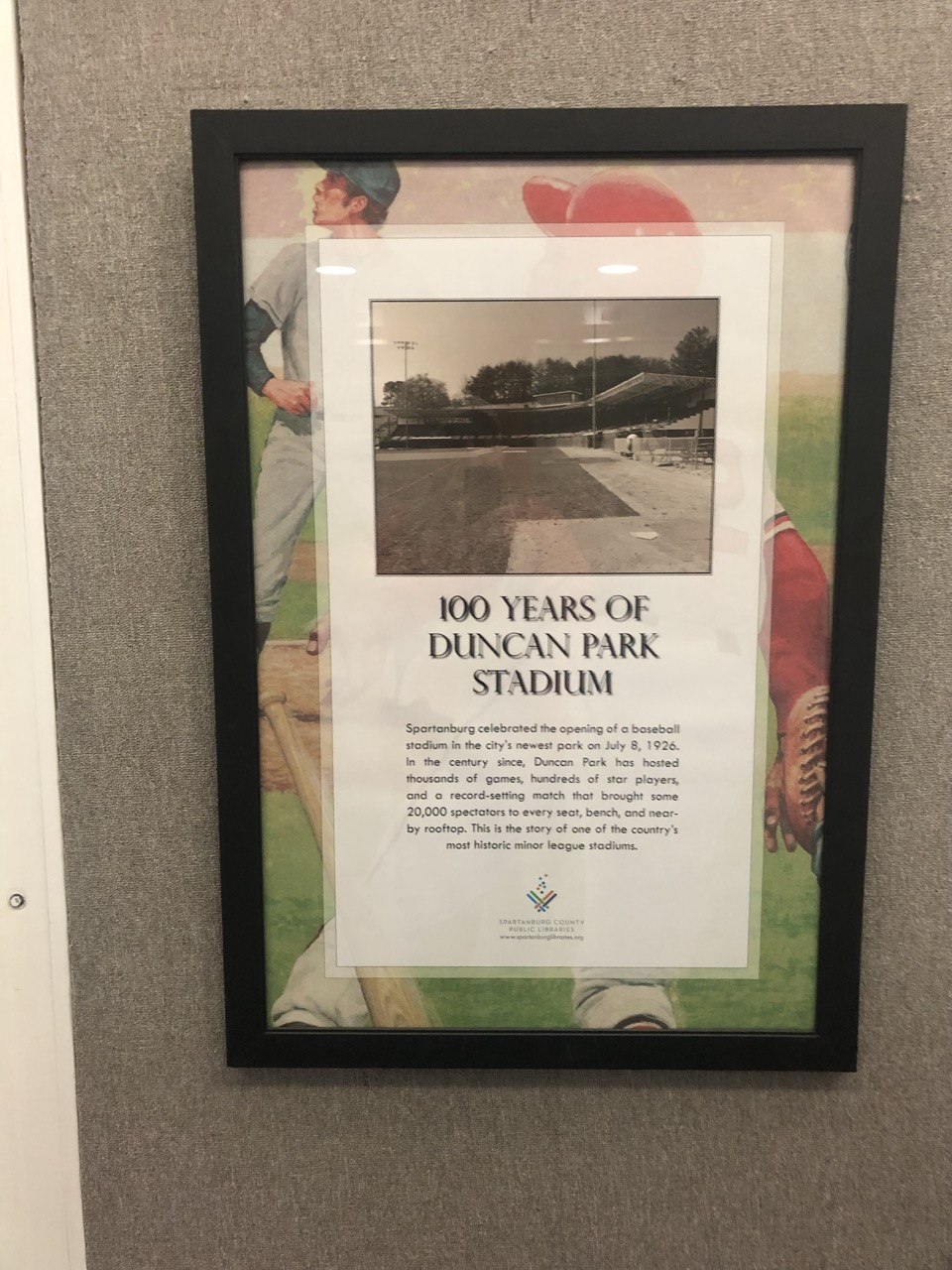

Duncan Park stadium, which had been extravagantly praised by Major League Baseball Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis when it had opened in the summer of 1926, was just over a decade old and was still regarded as one of the best ballparks in he country. That’s why it had been chosen as the location for the American Legion national championship series the summer before. The choice had been propitious beyond all expectations. So many fans attended the final game of the Legion Series in 1936 that they filled the grandstand, the bleachers, the grassy hillside beyond the bleachers, and even the tops of walls and the branches of the trees beyond the outfield wall. No sporting event in the Palmetto State had ever attracted such a crowd, and the citizens of Sparkle City expected another sellout.

The expectations were fulfilled. When the first pitch was thrown in the Yankees game that Wednesday afternoon, April 14, 1937, some 5,000 spectators were on hand, twice the seating capacity for which the stadium had been designed. The Herald reported that attendees “jammed into every available seat in the grand stand and bleachers and bulged out onto the embankment on the right field foul line or crowded into standing space along the left side of the playing field.”

The primary attraction was the New York team, which had won the 1936 World Series in five games against their cross-town rivals the New York Giants. The Yankees were to win again in 1937, and they had already won five World Series titles since 1923, so they were clearly a legendary team.

The 1937 Yankees included Iron Man Lou Gehrig on first, youngster Joe DiMaggio in the outfield, Bill Dickey behind the plate, Frankie “The Crow” Crosetti on the left side of the infield, and “age-defying” Tony Lazzeri on second base. Fellow Hall of Famers Lefty Gomez and Red Ruffing were in the pitching corps, and manager Joe McCarthy was also to become a member of the Hall of Fame. The team was to win almost twice as many games (102) as it would lose (52) in 1937, so to be in the audience on April 14th would be special. Even umpire Emmett Ormsby was worth seeing: in addition to being a favorite of the press and a veteran pitch caller who would also serve in the ’37 World Series, the Chicagoan was known by fans for his appearances as Santa Claus before his eleven children on Christmas, a performance duly reported by newspapers across the country during the holiday season.

The beginning of the game was less than promising for the World Series champs, who fielded “more like Wofford than the world’s No. 1 baseball team from the big town.” After failing to get a hit in the top of the first against Binghamton, the Yankees committed three errors in the bottom of the inning, and the score stood at 2-0 Triplets.

The Yanks began to rally, however, as any MLB team might be expected to. They held Binghamton scoreless in the second and third innings, and in the third Lou Gehrig threw out Triplets first baseman John Sturm at home as he tried to stretch a routine infield grounder into a scoring opportunity.

The World Series champs then scored five runs in the top of the fourth with a combination of walks and small ball hits by catcher Arndt Jorgens, second baseman Don Heffner—who was playing to give Tony Lazzeri, “the Rock of Gibraltar of the Yankee team,” a well deserved day off after having played in each spring training game up until the fourteenth—and Frankie Crosetti, the beneficiary of an error by the Triplets short stop.

The Binghamton team put up two more runs in the fifth, making the score 5-4, but the Yankees added two in the sixth on four more singles. There was no score in the seventh, after which the game was suspended so that the Yankees could make their train connection for a trip to Norfolk, Virginia, for yet another spring training game the next day. Even their mode of transportation was special for the Yankees since they traveled in four “special” rail cars, including one for the sports writers who accompanied them.

There were additional special attractions which no doubt induced some Spartanburg fans to attend the game at Duncan Park. One was the entertaining appearance of 235-pound Yankee pitcher Walter Brown, “who looked much like a big gray balloon out there as a strong wind whipped his baggy pantaloons and loose-fitting shirt,” according to Herald Sports Editor Bud Seifert. Brown crushed a ground rule triple to left field in the fourth inning, after which he provided a bonus spectacle as he “waddled over the platter” to score on a ball hit by Crosetti.

There were other, unexpected past and future connections to Duncan Park teams during 1937 spring training. For one, Mike Kelly, the popular player-coach of the Spartanburg Spartans in the 1920s and the manager of the first-ever tenant of Duncan Park stadium, was now the manager of the AA Syracuse Chiefs, an affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds, and the Chiefs were scheduled to play Binghamton the Monday after the Yankees game. Then the two teams would play the next day in Charlotte, where the Chiefs were holding their spring training.

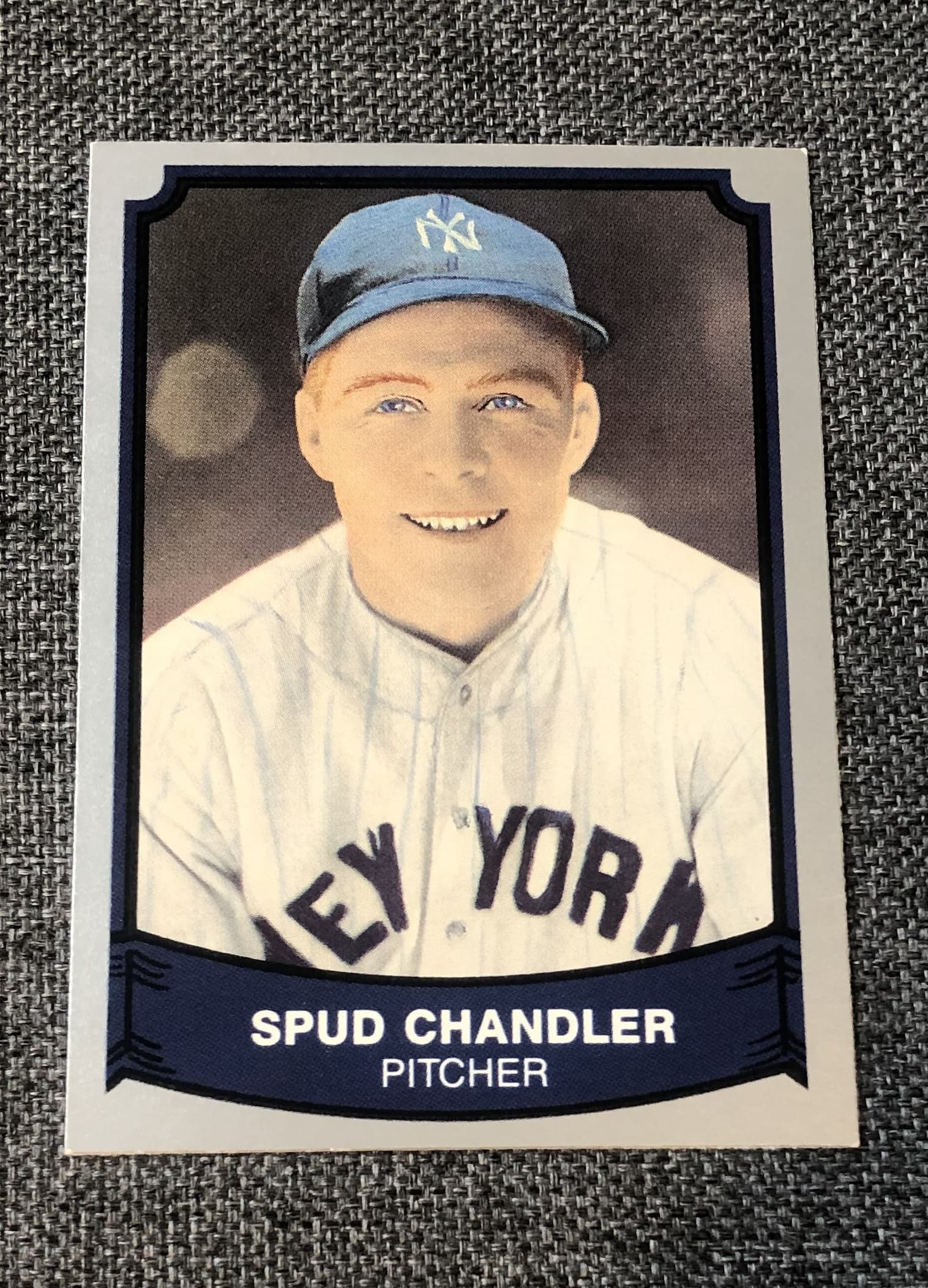

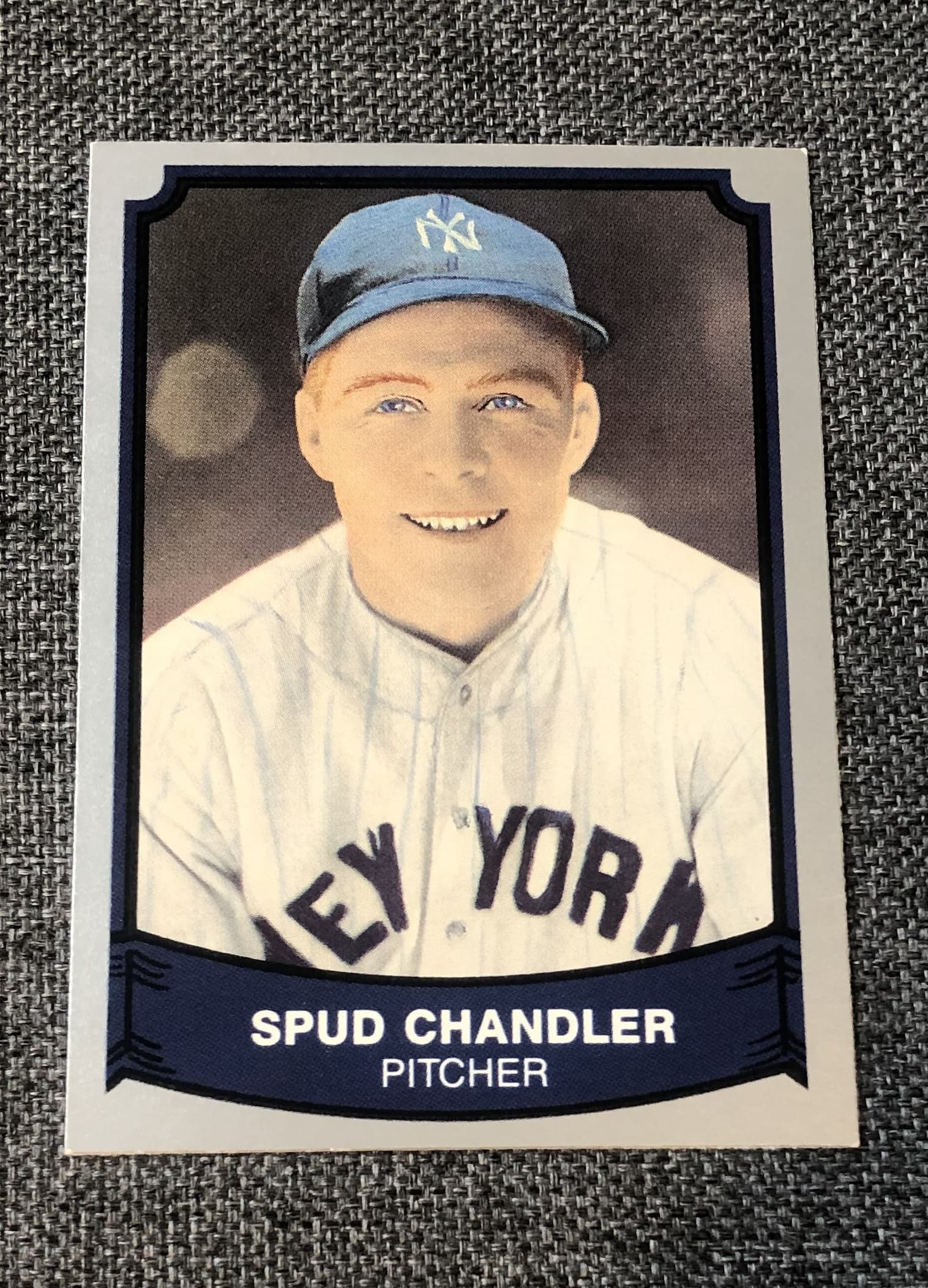

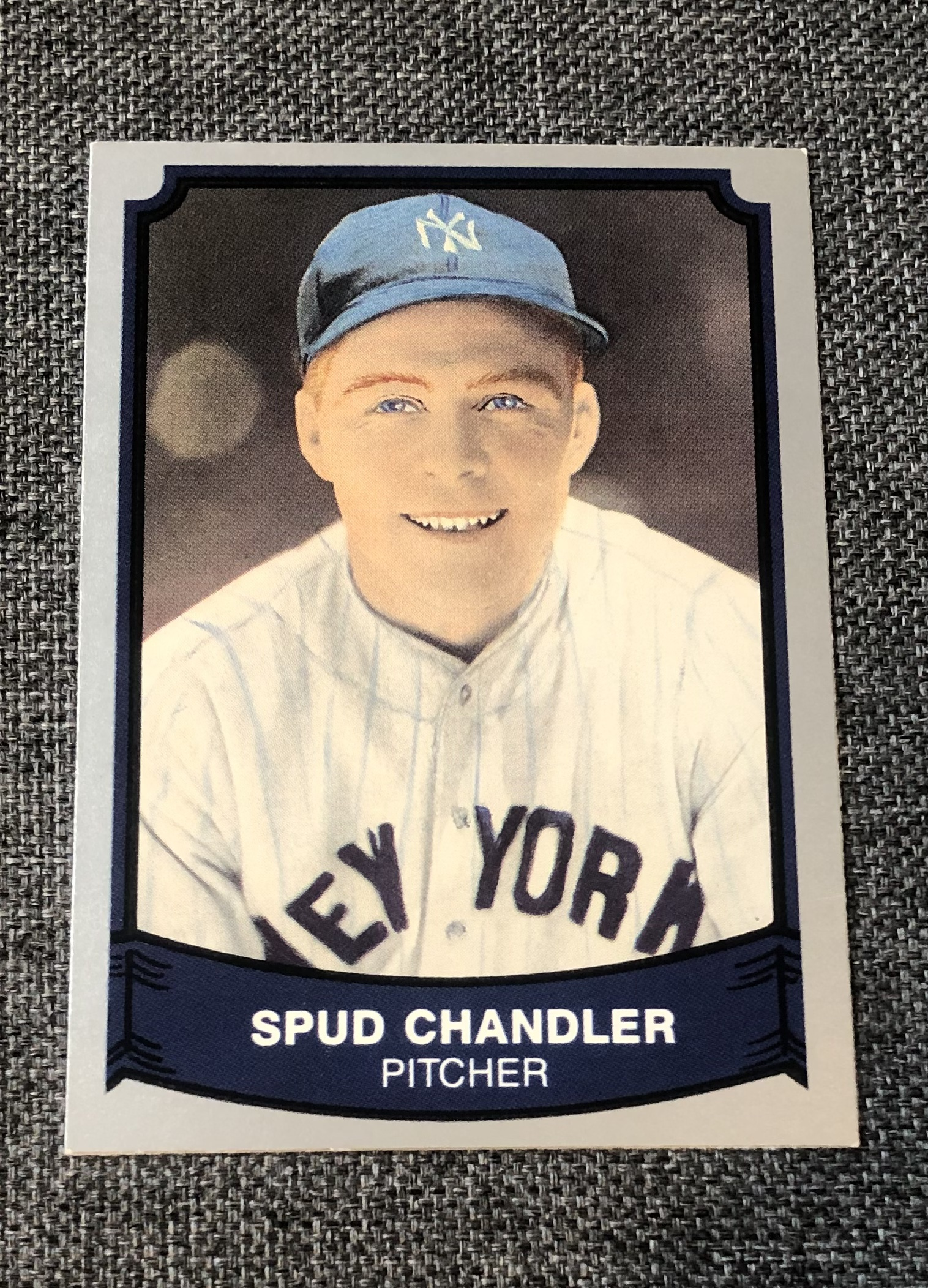

The Yankees in 1937 also fielded a 29-year-old rookie pitcher named Spurgeon “Spud” Chandler, a native of Commerce, Georgia, who had played both football and baseball for UGa. In the game on April 14th Chandler came in for Brown in the seventh inning, gave up no hits, and struck out 2. Spud was to play ten years for the Yankees; in 1943, his best year, he won 20 (all complete games), lost only 4, had the remarkably low ERA of 1.64, and was named American League MVP. In 1955 he would return to Spartanburg as manager of the Tri-State League Peaches in their last year at Duncan Park.

Other professional teams played ball at Duncan Park over the years. Among these were the barnstorming Jackie Robinson’s All-Stars and the well-known Negro League teams the Homestead Grays, the Philadelphia Stars, the Ethiopian Clowns, the Greenville Black Spinners, and others. Future “Beautiful Duncan Park” blog posts will be devoted to them.

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Author

Dr. Edwin C. Epps is a retired educator with more than forty years' experience in public school classrooms... He is the author of Literary South Carolina (Hub City Press, 2004) and a proud member of Phi Beta Kappa who believes in the value of the humanities in a rapidly changing world.