The Cincinnati Reds Take Down the Binghamton Triplets at Beautiful Duncan Park!

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

One of the surprising but familiar games played early on at Duncan Park stadium was that between the New York Yankees and the Binghamton Triplets on April 14, 1937, during spring training. The Yankees had won the 1936 World Series and five different World Series titles since 1923, and their lineup featured Lou Gehrig, Joe Dimaggio, Bill Dickey, Tony Lazzeri, Lefty Grove, and Red Ruffing.

The Cincinnati Reds Take Down the Binghamton Triplets at Beautiful Duncan Park!

One of the surprising but familiar games played early on at Duncan Park stadium was that between the New York Yankees and the Binghamton Triplets on April 14, 1937, during spring training. The Yankees had won the 1936 World Series and five different World Series titles since 1923, and their lineup featured Lou Gehrig, Joe Dimaggio, Bill Dickey, Tony Lazzeri, Lefty Grove, and Red Ruffing.

The Cincinnati Reds Take Down the Binghamton Triplets at Beautiful Duncan Park!

One of the surprising but familiar games played early on at Duncan Park stadium was that between the New York Yankees and the Binghamton Triplets on April 14, 1937, during spring training. The Yankees had won the 1936 World Series and five different World Series titles since 1923, and their lineup featured Lou Gehrig, Joe Dimaggio, Bill Dickey, Tony Lazzeri, Lefty Grove, and Red Ruffing. No wonder the stands were filled with twice the number of fans the stadium was designed for that day, and no wonder either that twenty-first century fans of baseball in the Hub City cherish that historic occasion in their hearts.

A less familiar game featuring another MLB team was played four days earlier, however, and few people today have any knowledge of that tilt. On April 10th the same Binghamton team that lost to the Yankees 7-4 took the field against the Cincinnati Reds, a team less legendary than the 1937 Yankees.

The 1936 Reds had finished that season with a record of 74 wins versus 80 losses and in fifth place in the National League, just one place above their sixth place finish in 1935. Manager Chuck Dressen was to win more than 1000 games as a manager and also managed the 1953 National League All-Star team, but his 1937 Reds featured few household names, and he himself was let go with a 51-78 record before the season was even over.

Catcher Ernie Lombardi was the team’s best offensive player, with a .333 batting average in 1936, soon to be followed by .334 in 1937. His teammates, though, were less skilled, posting a team batting average of .274, good for only 6th place in the 8-team National League in 1936, and .254 for 8th out of 8 in 1937.

Team pitching was also dismal. The winning percentage of the corps as a whole had been only 48% in 1936, and even Paul Derringer, who won 19 games during the season, also lost 19 games. Gene Schott, who had the second highest win total of 11 games, also lost as many as he won. The 1937 Reds, who were to have a winning percentage of only 36%, had five separate pitchers who were to lose 13 or more games during the season, and the team’s best pitcher would win only 12 games.

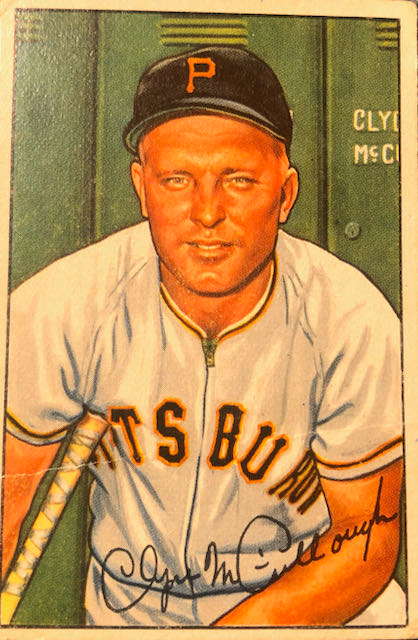

And what of the opposition Triplets? They looked promising, with 13 members of their 1936 roster having graduated on to MLB, and two dozen of their 1937 team were to go on to The Show for at least a few games. Nine members of the 1937 Triplets would bat over .300. Short stop Buddy Blair would hit .329 in 416 at bats, and catcher Clyde McCullough would hit for the same average in 210 plate appearances. Triplets pitching was less good however. The hurlers lost 2 more games than they won in 1937, and even right-hander George Washburn, who led the team with 13 wins, also led the team with losses, tying with teammate Fred Gay with 11.

So the incentives for Spartanburg fans to buy tickets for the three o’clock contest on the afternoon of April 10th were substantially less encouraging than those for the game four days later between the Triplets and the World Champion New York Yankees. The earlier game drew 2,000 fans, not bad for a stadium built for 2,500 maximum, but this figure was less half the 5,000 that attended the game featuring the pinstripes. Even so, though, most fans came purposefully to see the Triplets, a Class A Yankees team in the New York-Pennsylvania League who were training in Spartanburg rather than Florida or some more usual location for spring 1937. Also, the Triplets had won against the Augusta Tigers the day before in a 7-6 game in which they had smashed 15 base hits although the game had been called after eight innings because of unseasonably cold weather. Locals no doubt hoped for a similar display against the Reds.

For most of the game on the tenth it indeed looked like the Triplets would win for the second day in a row. Although Binghamton produced only 5 hits, they pitched well and carried a 2-1 lead into the ninth inning. Until the final inning, too, the visiting Reds were largely ineffectual at the plate, a situation noted by Sunday Spartanburg Herald-Journal Sports Editor Bud Seifert as “greatly to the glee of most of the crowd, which was decidedly partisan toward the Spartanburg-trained Triplets.”

Unluckily for the Trips, though, the Reds bats came alive in the ninth. Short stop Billy Myers, third baseman Jimmy Outlaw, and left fielder Phil Weintraub all hit home runs in the final inning, and the Reds tallied a total of five runs all together. The Triplets proved unable to answer, and the Major Leaguers won the game by a score of 6-2. Bud Seifert managed to offer a partial explanation by observing that “Although all the four-base blows were solid clouts, it is doubtful if any of them would have been homers if there had been a board fence around the outfield.”

Eventually there was actually a concrete fence around the outfield, but since it was constructed before building codes required reinforced concrete, it lacked footing, and the outfield grass often softened and became soggy when it rained, it began to slowly tilt inward pretty early on. Finally it toppled over of its own volition, depositing debris on the field where outfielders might easily have become the victims of the collapse. Fortunately there were no players inside the stadium when the accident occurred, and the concrete was replaced by a sturdy wooden structure.

One of the Reds stars in the ninth inning was 29-year-old Phil Weintraub, formerly of the New York Giants, up for his third stint in the Bigs. In 1936 Weintraub had batted .371 for the Rochester , including a 450-foot home run--one of twenty he smacked that year--that was the longest ever hit at Rochester up to then. Two years earlier the Chicago native had posted a robust .401 average for the Southern League Nashville Vols. Weintraub played for 7 years in the Majors and 16 in the Minors; in 1938, playing in 100 games for the Philadelphia Phillies, he hit .311 with 45 rbis.

Wild Bill Hallahan, who had pitched the previous seven years for the St. Louis Cardinals, pitched for the Reds against Binghamton. He pitched well for 8 innings at Duncan Park and would compile a 3-9 record with a 6.14 ERA for the Reds in 1937 as a 35-year-old. In 1931 he won 19 games for the Cardinals, best in the National League that year.

The Sunday Herald-Journal tried hard to drum up fan interest in the April 10th contest. Among the paper's strategies was a collection of largely random facts and statistics published in an article titled "Dressen Pushes Reds Hard in Exhibitions." Among the "facts" listed therein was that the Cincinnati short stop Charlie Gelbert had "shot part of his left foot off in a hunting accident in 1932, yet came back as well as ever." Another was that Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi "[b]y actual measurement" had a larger "schnozzle" than entertainer Jimmy Durante, one of whose hallmarks was the size of his ample nose. Only baseball fans would care.

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Author

Dr. Edwin C. Epps is a retired educator with more than forty years' experience in public school classrooms... He is the author of Literary South Carolina (Hub City Press, 2004) and a proud member of Phi Beta Kappa who believes in the value of the humanities in a rapidly changing world.