Who Was Bob Branson? The Story of a Spartanburg Sluggers Legend

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

And was he even Bob Branson? Newspaper accounts from the 1930s and ‘40s spell his surname variously as Branson, Brunson, and Brinson, and there is a better than even chance that there are other spellings out there that I have not encountered. Such is the ill-informed fate of many former Negro League and independent Black semipro ballplayers, and that is who Bob Branson—and yes, it is in fact Branson—was.

Who Was Bob Branson? The Story of a Spartanburg Sluggers Legend

And was he even Bob Branson? Newspaper accounts from the 1930s and ‘40s spell his surname variously as Branson, Brunson, and Brinson, and there is a better than even chance that there are other spellings out there that I have not encountered. Such is the ill-informed fate of many former Negro League and independent Black semipro ballplayers, and that is who Bob Branson—and yes, it is in fact Branson—was.

Who Was Bob Branson?

And was he even Bob Branson? Newspaper accounts from the 1930s and ‘40s spell his surname variously as Branson, Brunson, and Brinson, and there is a better than even chance that there are other spellings out there that I have not encountered. Such is the ill-informed fate of many former Negro League and independent Black semipro ballplayers, and that is who Bob Branson—and yes, it is in fact Branson—was.

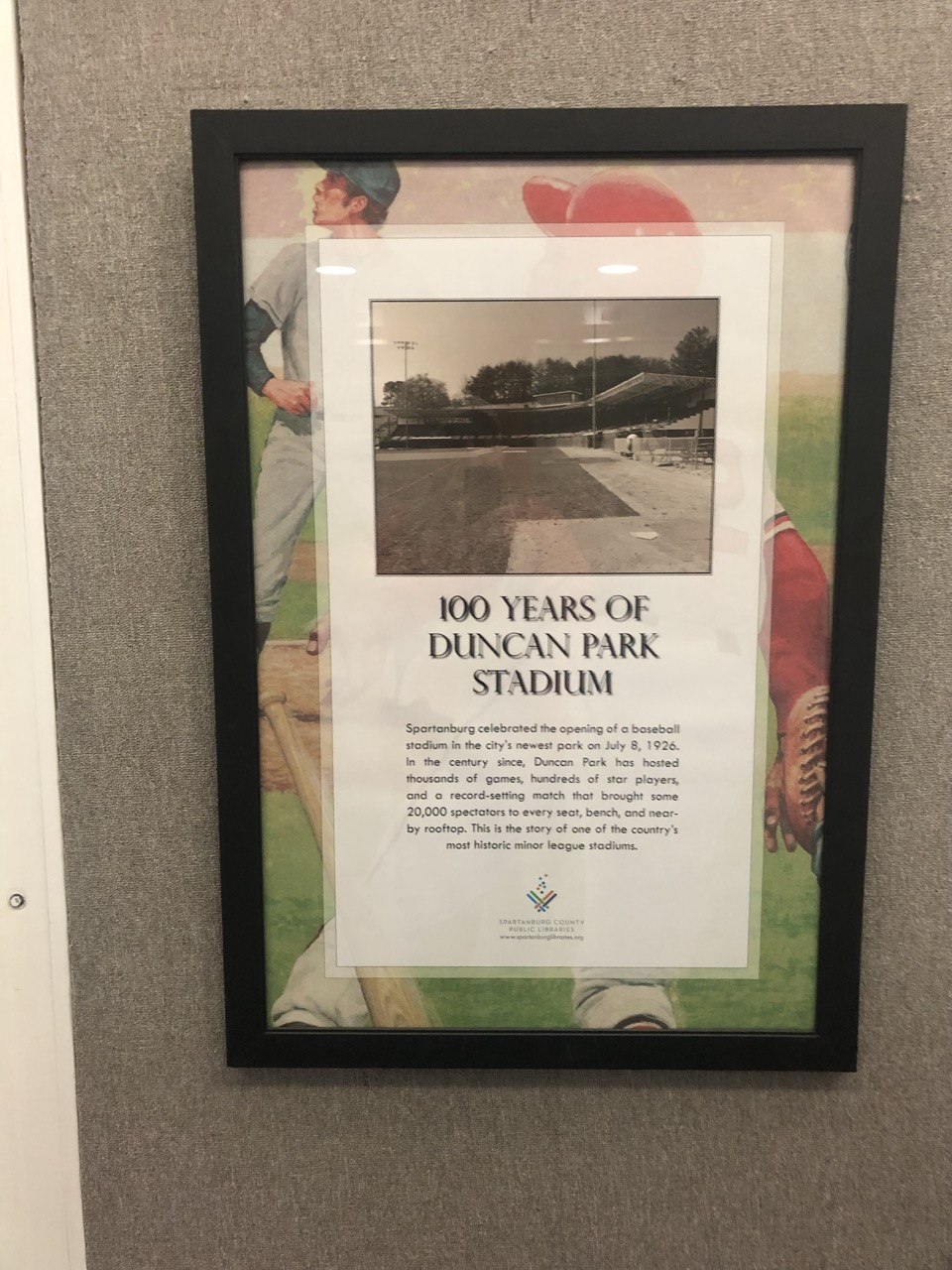

In sports reporters’ stories and notices of upcoming Spartanburg Sluggers games at Duncan Park and elsewhere, Bob Branson’s name is invariable preceded by his nickname “Lefty,” for he was one of the most accomplished left-handed pitchers in the South during the decade or so that he played for the Whitmires. Often also the adjective “sensational” preceded the “Lefty.”

How sensational was Bob Branson? For one thing his endurance was sensational. The first game that I have been able to document that he played in occurred on August 18, 1938. On that date he pitched against the Gastonia Tigers at Duncan Park. The Sluggers won that game by a score of 4-0. Branson continued to pitch for the next fourteen years, during most of that time for the Sluggers, but he also played for a U. S. Army team during World War II and spent some time too with the Atlanta Black Crackers.

The last game that I can verify Branson played in took place on June 5, 1952, when he pitched against the Charlotte ABC’s in Duncan Park stadium. The Sluggers tied that game 16-16 in what must have been a rollicking affair. The reporter who covered the game for the local papers testified to Branson’s ongoing expertise by calling him “the Satchel Paige of the South.”

The reporter’s nickname for Bob Branson indicates the second reason that he was sensational: he clearly had exceptional skills as a pitcher. His over all record is unknown since Black semipro statistics are buried in the shadows of the imperfect coverage of Black teams and players by reporters for White-owned newspapers during the Jim Crow era, especially in the South. There were also few Black-owned papers, and the one that did exist in Spartanburg in the 1920s exists today in only a handful of extant copies that survive. Still, there is enough reliable information in the records that do exist to verify the skill of the remarkable Mr. Branson.

One indication of Branson’s prowess comes from his place on the roster of the 1945 U. S. Army team representing the 92nd Infantry Division. That team, Champions of the MTO (Mediterranean Theater of Operations), included no fewer than five players from professional Negro League teams: Willis “Red” Applegate (Pitcher, Newark Eagles); Johnny L. Hundley (2nd Base, Cleveland Buckeyes); J. Quincy “Bud” Barbee (1st Base, Baltimore Elite Giants); James E. “Joe” Greene (Catcher, Kansas City Monarchs); and Joseph J. Siddle (1st Base, also the Monarchs). In late September Minor league Baseball players Daniel J. “Dan” Perlmutter (1st Base, 4 teams in 3 leagues, 1947-1949) and Paul Lange (Pitcher, 2 teams in 2 leagues, 1946-1947) also joined the 92nd Infantry team when they played against the ETO (European Theater of Operations) Champions.

Given the competitive nature of military service in general, being chosen to play for an Infantry Division Championship team is itself a confirmation of a substantial degree of talent on the diamond. The fact that such a team also featured five Negro League players and two future Minor Leaguers provides additional evidence that Bob Branson was indeed a good player. His military teammate Bud Barbee played for 8 years in the Negro National League II, primarily for the New York Black Yankees; and catcher Joe Greene played professional ball for 11 years, mostly for the legendary Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League, for whom he played in 3 All-Star games, spent 6 years in the top 10 home run sluggers, and possessed one of the top 10 fielding percentages as a catcher. Playing alongside such players not only validated Bob Branson’s own abilities; it must have also sharpened his talents as well as he watched his teammates play on the field.

Branson had played five years for the Sluggers before he was drafted into the Army, and he played another five years after the war, plus at least one additional game in 1952. He was one of the best left-handed pitchers in the region, throwing at least 10 strikeouts in at least 13 verifiable games. On September 11, 1946, he struck out an unbelievable 22 batters in a 13-1 win against the Greenville Giants. This was no fluke: he also struck out 22 against the North Carolina All-Stars at Duncan Park on August 29, 1949; another 21 versus the Orangeburg Tigers on their home field on July 3, 1948; 16 against the Asheville Blues on April 24, 1950; 15 against the Greenville Giants on August 25, 1948; and even 14 against the well-known Atlanta Black Crackers on August 11, 1942. Small wonder that newspaper accounts referred to Branson as a “crack pitching ace” and “the League’s outstanding pitcher.” On July 12, 1948, in the midst of what was likely Branson’s best year for the Sluggers, the team celebrated “Lefty Branson Night” at Duncan Park stadium. In the spring of that year the lefty had even thrown a no-hitter in a 15-0 win against Valdosta.

Nor was the pitcher a slouch at the plate. In the same game in which he pitched his no-hitter, Branson hit three triples and had 2 other hits. Three weeks before he threw the no-hitter, on April 5, 1948, he hit 2 triples against the Greenville Giants. On May 6, 1949, he hit a grand slam against the Lyman Red Sox, probably a Textile League team. On July 14, 1949, although he pitched a losing effort in a game won 2-1 by the Asheville Blues, Lefty Branson tripled home the Sluggers’ lone run. The next year, on April 10, 1950, although he lost again, this time against the Negro League Baltimore Elite Giants by a score of 14-8, he also managed to belt a three-run homer.

Such feats as these endeared Bob Branson to the fans at Duncan Park and elsewhere. People came to the stadium to see him play, and he drew White spectators as well as Black ones. Attendance records are hard to come by for small-town Black baseball teams, but Upstate newspapers reported attendance of 1,100 against the Greenville Spinners on May 26, 1941; 1,000 against the Charlotte Red Sox on August 3, 1942; and 1,000 against the Black Spinners again on September 7, 1942—this in a stadium built for 2,500 but all achieved during some of the darkest days of World War II when many men were away and their families hunkered down at home with little money to spend on a baseball game. It is worth noting too that attendance was robust enough to attract teams like the Atlanta Black Crackers, Atlanta All-Stars, Homestead Grays, Richmond Giants, North Carolina All-Stars, and Baltimore Elite Giants to play at Duncan Park. Also, the Sluggers played long-running series against the Greenville Black Spinners and Giants, the Asheville Blues and Black Tourists, and teams from Charlotte and Orangeburg at a time when team transportation was either via uncomfortable and inconvenient railways or crowded and un-air conditioned buses which could or would not stop along the way for Black passengers to buy snacks or meals. Lefty Bob Branson was one of the prime attractions that filled the grandstand during these times.

One final fact about Bob Branson deserves mention: he almost made it to the Major Leagues. After he returned from service at the end of World War II, he was actively recruited by Major League scouts. Newt Whitmire, the Sluggers owner, owned a hotel and restaurant at 117 Short Wofford Street in downtown Spartanburg, and Branson worked at the restaurant as well as played ball for Newt after the war. Because of Newt’s reputation and his relationships with many Negro League managers and owners, many Major League executives also knew about Bob Branson and wanted him for their own teams. They became a familiar sight at Newt’s Place.

It is worth remembering as well that 1947 was the year that Jackie Robinson integrated the Major Leagues, and many managers and coaches in the American and National Leagues were already on the lookout for talented Black players, aware that the exclusion of Black players from the Majors was about to end. Bob Branson played for the Sluggers after the war, but in 1946 and 1947 he also played outfield and pitched for the Atlanta Black Crackers, and his time as a Black Cracker inevitably gave him greater exposure in the larger market of Atlanta than he received in Spartanburg. So there is little wonder that scouts and recruiters beat a path to the venue where Branson worked in the Piedmont of South Carolina.

Why didn’t Bob graduate to a Major League team where he would have made more money and achieved greater renown? He was certainly good enough to have merited at least a tryout or a spot on a Class A Minor League roster.

The fly in the ointment was Bob’s girlfriend Lil. As much as Bob loved baseball, he apparently loved Lil more. She wanted to stay with him in Spartanburg and not go gallivanting off to Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Kansas City, or New York—and stay in Spartanburg Bob Branson did. He continued to play for the Sluggers until the 1960s, died at age 87 on June 17, 2003, and lies at rest today in Heritage Memorial Gardens in Roebuck, South Carolina.

Dr. Edwin C. Epps

Author

Dr. Edwin C. Epps is a retired educator with more than forty years' experience in public school classrooms... He is the author of Literary South Carolina (Hub City Press, 2004) and a proud member of Phi Beta Kappa who believes in the value of the humanities in a rapidly changing world.